Kneading New Life Into an Old Tradition

story by Donna Hecker & photography by Talitha Schroeder

Behold the beaten biscuit — a delicate round of barely-browned pastry, diminutive in size, marked with the de rigueur three x three pinpricks made by the slender tines of a cocktail fork, preferably from Mother’s silver service. Rarely seen most of the year, the beaten biscuit sallies forth at holiday parties, split in half, swaddling a few precious slivers of country ham; and is much relished by a diminishing segment of Southern society.

But wait, let’s start all over.

Behold the beaten biscuit — a sturdy staple made of a few common ingredients; called a work biscuit and tucked into the pockets of laborers heading to the fields or the docks for a long day of toil. Durable and long-lasting, a possible descendant of hardtack, the beaten biscuit is thought to have made its earliest appearance along the Chesapeake shore and North Carolina lowlands in the late 1700s.

The mystery of how party biscuits and work biscuits converged has yet to be solved but perhaps it was because the primary ingredients: flour, lard or butter, and water or milk were readily available at a time when leavening agents were not. Mary Randolph included a recipe for the biscuits, which she called Apoquiniminc Cakes, in her 1824 book, The Virginia Housewife; an even earlier version appeared in Harriett Pinckney Horry’s Receipt Book, written around 1770.

This much we do know: beaten biscuits were literally beaten, the object being to work the dough over and over until it blistered and popped, resulting in a toothsome biscuit that was the pride of many a Southern hostess. Early accounts describe leveled tree stumps and axe handles, later replaced by custom-built biscuit tables topped with a granite slab and hinged cover, and wooden mallets or rolling pins.

And this we also know: in the antebellum South, beaten biscuits were the center of attention on dining room tables precisely because they required intense physical effort, effort that could only be extracted when the person expending it was either enslaved or in servitude.

Jai Jordan, site manager of Historic Brattonsville in York County, South Carolina, points out that “biscuits meant you could afford kitchen help. Biscuits at breakfast meant someone got up and made them for your pleasure. It was a sign of wealth.”

And Toni Tipton-Martin picks up the thread in Jubilee — “remembered in the Slave Narratives as the ‘grandfather of all afternoon tea refreshments’, beaten biscuits held a place of honor in black cookbooks for generations, presumably because white families in the Old South always considered beaten biscuits a luxury and a hostess’s pride.”

In fact, Abbie Fisher, a formerly enslaved woman who moved from Alabama to San Francisco and wrote What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, began her cookbook with a recipe for Maryland Beat Biscuit.

So perhaps it’s no coincidence that the first mechanical biscuit brakes were manufactured in the years following the Civil War. Many Bluegrass households, including Holly Hill Inn, possess models made by J.A. DeMuth of St. Joseph, Missouri, and a surprising number of them are still in use.

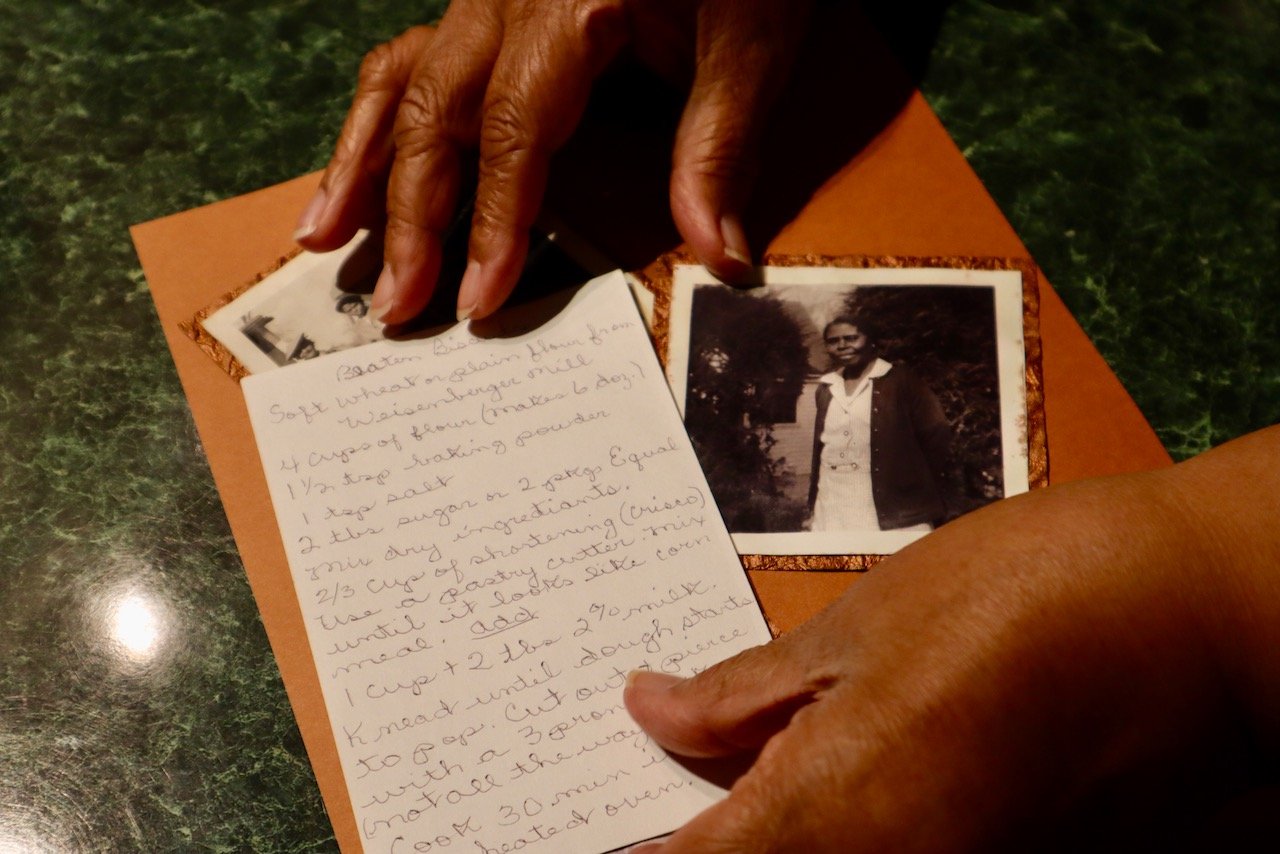

Billie Rothel-Martin’s family biscuit brake

Given their history, we wondered whether beaten biscuits meant different things to our Black and white neighbors, but everyone we talked to had fond memories of eating them, especially on holidays and other special occasions.

Glenn Wilson, who works with us at Holly Hill Inn, used to crank the rollers on his great aunt’s machine and prick the biscuits as they made their way to the oven. Glenn says that Sue Collins Russell made biscuits for many of the horse farms in Woodford County, and she often them sold along with country hams that she cured in her backyard smokehouse.

Midway’s Helen Rentch still bakes them.

Some of us grew up on them. My family had them every other Sunday for dinner at Grandmother Roach’s. They were made by Sarah (Sadie) Johnson of Johnson St., on a machine to which my grandfather had attached a big motor but before that, Daddy grew up hand-cranking the machine for Sarah.

Helen fears that beaten biscuits will “surely die out before long if something is not done.” A fear echoed by Billie Rothel-Martin who helped her cousin Lizzie (Elizabeth Craig) with her baking.

Recipe written down by her sister Drucilla Darneal and photo of her cousin, Lizzie (Elizabeth Craig)

I think it’s just like a dying thing that was really important years ago… there wasn’t much to do in Midway and I loved to roll the dough and hear the air bubbles pop. That was one of my favorite things.

— Billie Rothel-Martin

Midway’s most famous beaten biscuit expert is octogenarian Charles Logan. Mr. Logan has shared his know-how at several workshops organized to benefit The Homeplace, a local retirement community. He came to beaten biscuits late in life, and indulged his love of tinkering by refurbishing old machines, which led to baking for friends and family.

You’re not going to get rich making them. I made them for love more than anything else.

Mr. Logan’s children, especially his son Chuck, loved watching their next door neighbor Rosa Thomas roll out beaten biscuits on her enclosed porch, to be sold to the well-to-do families in town. Chuck often waited at Mrs. Thomas’s back door until she slipped him a few biscuits, still hot from the oven.

When Ouita Michel first met Mr. Logan, and admitted she’d never made beaten biscuits, he sold her a restored kneader for a dilapidated base left behind on Holly Hill Inn’s front porch when she and Chris moved in. Ouita soon learned that Midway was full of old biscuit brakes and was known as a beaten biscuit zone, where families served them with country ham on special occasions.

As Billie Rothel-Martin told us, “It’s not just a beaten biscuit. It’s the country ham that goes on them. You can't have one without the other.”

Though often derided for their bland flavor and dry texture, beaten biscuits are the perfectly neutral foil for a slice of well-aged Kentucky ham. Many Bluegrass families, like Glenn’s Aunt Sue’s, once cured their own hams, and some younger farmers are taking up the craft again.

Midwegians who still make beaten biscuits swear by the soft winter wheat flour milled at nearby Weisenberger Mill. Perched on the South Fork of Elkhorn Creek, the mill is in its sixth generation of family ownership under Mac Weisenberger, who says soft winter wheat — so well suited to Southern growing conditions — has a naturally low gluten content, perfect for biscuits.

Central Kentucky was once dotted with grist mills for grinding corn into meal; since locally milled flour was much rarer, it’s possible that Weisenberger Mill’s proximity contributed to Midway’s beaten biscuit tradition, a tradition that Ouita Michel is on a mission to maintain.

Because as William Faulkner said, “The past is never dead. In fact, it’s not even past.” But it’s the latter part of his quote that truly resonates and usually goes unmentioned. “All of us labor in webs spun long before we were born, webs of heredity and environment, of desire and consequence, of history and eternity.”

If the web was spun before our time, and yet we still labor, let’s endeavor to enrich its design by weaving a clearer, fuller picture of how the foods we prepare and consume today were shaped by a past which lives on.

Contemporary food writers like Toni Tipton-Martin help us understand the complex and disturbing stories behind dishes like beaten biscuits. They also prompt us to honor and respect the memory of those whose hands created food for the nourishment of others; usually at the expense of their own families, and generally with no say in the matter.

We have agency today, and an obligation, to acknowledge the ones who came before us. As we gather with friends and family, let’s knead new life into an old tradition by trying our hand at beaten biscuits. And as we pound the dough until it blisters and pops, let’s also strike a blow for remembering, for truth-telling, and for venerating the dignity of working hands.

© 2024, Holly Hill Inn/Ilex Summit, LLC and its affiliates, All Rights Reserved

Related Content

Beaten Biscuit Recipe

Knead new life into an old tradition and try your hand at beaten biscuits.